We often think of pollution in terms of smoke, plastic waste, or oil spills. But there’s another form of pollution that’s nearly invisible—and it’s happening right in our homes every time we do laundry. The simple act of washing clothes, especially those made of synthetic materials, is releasing billions of microscopic plastic particles into the environment. These particles, known as microplastics, are now one of the largest sources of pollution in the modern world.

What Are Microplastics?

Microplastics are plastic particles smaller than 5 millimetres in size, often much tinier. They come in two main forms:

-

Primary microplastics: Intentionally manufactured small plastics, such as microbeads used in cosmetics or industrial abrasives.

-

Secondary microplastics: Formed when larger plastic products—like bottles, bags, or textiles—break down into smaller fragments over time due to wear, sunlight, and friction.

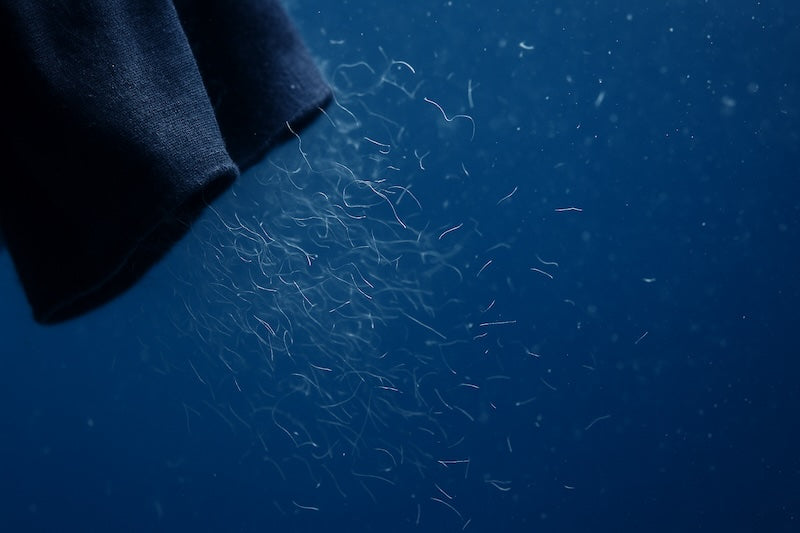

In the case of clothing, microplastics refer mainly to microplastic fibres—ultra-fine threads that shed from synthetic fabrics such as polyester, nylon, acrylic, or spandex. Every synthetic garment—whether a fleece jacket, athletic T-shirt, or leggings—is made up of countless filaments thinner than a human hair. During wear and washing, friction and heat cause these filaments to break loose and escape into wastewater systems.

A single wash load of synthetic clothing can release up to 700,000 microplastic fibres, according to Napper & Thompson (2016).1 These fibres are so small that they easily pass through wastewater treatment filters and flow directly into rivers and oceans.

The Scale of Microplastic Pollution

-

35% of all microplastics in the ocean originate from synthetic textiles, according to the IUCN (Boucher & Friot, 2017).2

-

Over 500,000 tonnes of microplastics are released globally each year from household laundry alone (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).3

-

Studies by Hartline et al. (2016) found that a single fleece jacket can shed up to 250,000 plastic fibres in one wash.4

Once released, these microscopic particles travel through waterways, accumulate in marine ecosystems, and even rise into the atmosphere. Microplastics have been discovered in Arctic snow, Himalayan glaciers, rainwater, and even human bloodstreams, confirming their pervasive global spread (Bergmann et al., 2019; Leslie et al., 2022).56

Why They’re Dangerous

Persistent and Indestructible: Unlike natural fibres, microplastics don’t biodegrade. Instead, they fragment into smaller and smaller particles—down to nanoplastics—that can persist for centuries.

Toxic Carriers: Microplastics attract and absorb pollutants like pesticides, heavy metals, and industrial chemicals, becoming vehicles for toxins in marine environments (Henry et al., 2019).7

Harm to Wildlife: Fish, plankton, and seabirds ingest microplastics, mistaking them for food. These particles can block digestive tracts, reduce nutrient absorption, and introduce toxins into the food chain (Browne et al., 2011).8

Human Exposure: Microplastics have been found in human lungs, blood, and placentas, raising concerns about chronic exposure. While research is still evolving, studies suggest potential links to inflammation, hormone disruption, and cellular damage (Leslie et al., 2022).6

What You Can Do

While systemic change in textile manufacturing and policy is critical, individual choices matter too. Here are simple steps you can take to reduce microplastic pollution:

-

Wash Less and Wash Cold: Frequent and hot washing increases fibre shedding. Opt for gentle cycles and air out clothes between wears.

-

Use Microplastic Filters or Bags: Devices like Guppyfriend and Cora Ball can capture up to 50% of shed fibres per wash (Ocean Wise Research, 2020).9

-

Buy Natural Fabrics: Choose cotton, hemp, linen, or wool—fibres that biodegrade naturally and don’t persist as microplastics.

-

Avoid Fast Fashion: Low-cost, synthetic garments shed more fibres and wear out quickly. Invest in quality pieces that last.

-

Line Dry Instead of Tumble Drying: Air drying reduces friction and fibre release.

-

Support Transparent Brands: Back companies that disclose their materials and actively seek sustainable alternatives.

Every small step adds up—reducing not just your environmental footprint, but also the long-term chemical load on our shared ecosystems.

At The Rugged Soul, we recognise that every garment has an unseen footprint. While we’re not yet a fully sustainable brand, we’re making conscious strides in that direction—using natural fabrics like cotton canvas, hemp, and cotton-linen blends, and designing small-batch, timeless collections that reduce waste.

By avoiding synthetic-heavy fabrics and choosing materials that age beautifully instead of polluting invisibly, we aim to lessen our contribution to the global microplastic problem. Through our storytelling and educational content, we encourage mindful ownership—buy less, buy better, and care longer.

We may not be perfect, but we’re deliberate in our intent to design for longevity, durability, and a lighter environmental impact.

Microplastic pollution is one of the most insidious forms of environmental damage today—tiny, invisible, and everywhere. It’s a reminder that sustainability isn’t just about how our clothes are made, but what happens to them every time we use them.

Every wash matters, every fibre counts—and every conscious choice helps rewrite the story of fashion’s invisible footprint.

Footnotes

-

Napper IE, Thompson RC. Release of synthetic microplastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2016. ↩

-

Boucher J, Friot D. Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN Report. 2017. ↩

-

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. ↩

-

Hartline NL, et al. Microfiber Masses Released from Polyester Fleece during Laundering. Environmental Science & Technology. 2016. ↩

-

Bergmann M, et al. Plastic pollution in the Arctic snow. Nature Geoscience. 2019. ↩

-

Leslie HA, et al. Discovery and quantification of plastic particles in human blood. Environment International. 2022. ↩ ↩2

-

Henry B, et al. Microfiber pollution and the apparel industry. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2019. ↩

-

Browne MA, et al. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines worldwide: Sources and sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. 2011. ↩

-

Ocean Wise Research. Microfibre Reduction Devices: Effectiveness and Consumer Use. 2020. ↩

Share:

DIY - Waterproofing Wax for Canvas Jackets